May 30, 2009

Larry Solomon: ENRON’S Other Secret

By Lawrence Solomon, The Financial Post

We all know that the financial stakes are enormous in the global warming debate - many oil, coal and power companies are at risk should carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases get regulated in a manner that harms their bottom line. The potential losses of an Exxon or a Shell are chump change, however, compared to the fortunes to be made from those very same regulations.

Some of the climate-change profiteers are relatively unknown corporations; others are household names with only their behind-the-scenes role in the climate-change industry unknown. Over the next few weeks, in an extended newspaper series, you will become familiar with some of the profiteers, and with their machinations. This series begins with Enron, a pioneer in the climate-change industry.

Almost two decades before President Barack Obama made “cap-and-trade” for carbon dioxide emissions a household term, an obscure company called Enron - a natural-gas pipeline company that had become a big-time trader in energy commodities - had figured out how to make millions in a cap-and-trade program for sulphur dioxide emissions, thanks to changes in the U.S. government’s Clean Air Act. To the delight of shareholders, Enron’s stock price rose rapidly as it became the major trader in the U.S. governmentís $20-billion a year emissions commodity market.

The climate-change industry - the scientists, lawyers, consultants, lobbyists and, most importantly, the multinationals that work behind the scenes to cash in on the riches at stake - has emerged as the worldís largest industry. Virtually every resident in the developed world feels the bite of this industry, often unknowingly, through the hidden surcharges on their food bills, their gas and electricity rates, their gasoline purchases, their automobiles, their garbage collection, their insurance, their computers purchases, their hotels, their purchases of just about every good and service, in fact, and finally, their taxes to governments at all levels.

These extractions do not happen by accident. Every penny that leaves the hands of consumers does so by design, the final step in elaborate and often brilliant orchestrations of public policy, all the more brilliant because the public, for the most part, does not know who is profiteering on climate change, or who is aiding and abetting the profiteers.

Enron Chairman Kenneth Lay, keen to engineer an encore, saw his opportunity when Bill Clinton and Al Gore were inaugurated as president and vice-president in 1993. To capitalize on Al Goreís interest in global warming, Enron immediately embarked on a massive lobbying effort to develop a trading system for carbon dioxide, working both the Clinton administration and Congress. Political contributions and Enron-funded analyses flowed freely, all geared to demonstrating a looming global catastrophe if carbon dioxide emissions werenít curbed. An Enron-funded study that dismissed the notion that calamity could come of global warming, meanwhile, was quietly buried.

To magnify the leverage of their political lobbying, Enron also worked the environmental groups. Between 1994 and 1996, the Enron Foundation donated $1-million to the Nature Conservancy and its Climate Change Project, a leading force for global warming reform, while Lay and other individuals associated with Enron donated $1.5-million to environmental groups seeking international controls on carbon dioxide.

The intense lobbying paid off. Lay became a member of president Clinton’s Council on Sustainable Development, as well as his friend and advisor. In the summer of 1997, prior to global warming meetings in Kyoto, Japan, Clinton sought Lay’s advice in White House discussions. The fruits of Enron’s efforts came soon after, with the signing of the Kyoto Protocol.

An internal Enron memo, sent from Kyoto by John Palmisano, a former Environmental Protection Agency regulator who had become Enron’s lead lobbyist as senior director for Environmental Policy and Compliance, describes the historic corporate achievement that was Kyoto.

“If implemented this agreement will do more to promote Enron’s business than will almost any other regulatory initiative outside of restructuring of the energy and natural-gas industries in Europe and the United States,” Polisano began. “The potential to add incremental gas sales, and additional demand for renewable technology is enormous.”

The memo, entitled “Implications of the Climate Change Agreement in Kyoto and What Transpired,” summarized the achievements that Enron had accomplished. “I do not think it is possible to overestimate the importance of this year in shaping every aspect of this agreement,” he wrote, citing three issues of specific importance to Enron which would become, as those following the climate-change debate in detail now know, the biggest money plays: the rules governing emissions trading, the rules governing transfers of emission reduction rights between countries, and the rules governing a gargantuan clean energy fund.

May 29, 2009

Bloomberg on Exxon Mobil: Energy and Climate Realists

By Joe Carroll, Bloomberg

Exxon Mobil Corp., the world’s largest refiner, said the transition away from oil-derived fuels is probably 100 years away.

Petroleum-based fuels including gasoline and diesel, as well as hydrocarbons such as coal and natural gas, will remain the dominant sources of energy for factories, offices, homes and cars for decades because there are no viable alternatives, Chief Executive Officer Rex Tillerson told reporters today after Exxon Mobil’s annual shareholders meeting in Dallas.

In the U.S., which burns a quarter of global oil supplies, consumers probably face higher fuel prices if lawmakers impose greenhouse-gas rules that inflate fuel-production costs, Tillerson said. A plan introduced by Democrats this month would allocate a limited number of emission credits to refiners and electricity producers, with the aim of curbing greenhouse gases.

“The oil-gas-refining side of the business received a very, very small amount of the allocations, which means that sector will bear more of the costs more immediately,” Tillerson said. “If we’re going to place a price on carbon, let’s do that in the most efficient way. A carbon tax is more efficient than a tax that’s applied by way of a cap-and-trade mechanism.”

Tillerson, 57, said lawmakers are hurrying to restrict greenhouse gases when many scientific questions surrounding the global warming issue remain unresolved.

“The point of conflict that I find more often than not are the projections that some make regarding how serious the problem may become and at what pace of acceleration it may occur,” Tillerson told investors at the shareholders meeting. “All of those models have deficiencies in the way theyíre constructed and the assumptions that go into the models and the limitations of the data.”

Tillerson, a University of Texas-trained engineer, said climate change is a “serious risk-management issue” for Exxon Mobil. The company will continue to fund scientific research into climate science and the impact of greenhouse gases on the atmosphere, he said.

“We’re going to be very forthright in not accepting something that is not completely scientifically proven,” Tillerson said. “We’re not skeptics. We’re just approaching this the way we would approach any scientific challenge, and it’s a serious challenge.” Read more here.

May 28, 2009

New Solar Cycle Prediction: Fewer Sunspots, But Not Necessarily Less Activity

May 27th, 2009 By Tony Phillips

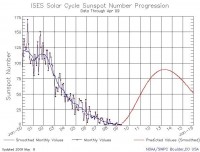

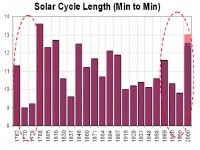

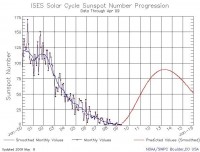

An international panel of experts has released a new prediction for the next solar cycle, stating that Solar Cycle 24 will peak in May 2013 with a below-average number of sunspots. Led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and sponsored by NASA, the panel includes a dozen members from nine different government and academic institutions. Their forecast sets the stage for at least another year of mostly quiet conditions before solar activity resumes in earnest.

“If our prediction is correct, Solar Cycle 24 will have a peak sunspot number of 90, the lowest of any cycle since 1928 when Solar Cycle 16 peaked at 78,” says panel chairman Doug Biesecker of the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center, Boulder, Colo.

It is tempting to describe such a cycle as “weak” or “mild,” but that could give the wrong impression. “Even a below-average cycle is capable of producing severe space weather,” says Biesecker. “The great geomagnetic storm of 1859, for instance, occurred during a solar cycle of about the same size we’re predicting for 2013.”

This plot of sunspot numbers shows the measured peak of the last solar cycle (Solar Cycle 23) in blue and the predicted peak of the next solar cycle (24) in red. Credit: NOAA/Space Weather Prediction Center.

The 1859 storm—named the “Carrington Event” after astronomer Richard Carrington who witnessed the instigating solar flare—electrified transmission cables, set fires in telegraph offices, and produced Northern Lights so bright that people could read newspapers by their red and green glow. A recent report by the National Academy of Sciences found that if a similar storm occurred today, it could cause $1 to 2 trillion in damages to society’s high-tech infrastructure and require four to ten years for complete recovery. For comparison, Hurricane Katrina caused $80 to 125 billion in damage.

The latest forecast revises a prediction issued in 2007, when a sharply divided panel believed solar minimum would come in March 2008 and would be followed by either a strong solar maximum in 2011 or a weak solar maximum in 2012. Competing models of the solar cycle produced different forecasts, and researchers were eager for the sun to reveal which was correct.

“It turns out that none of the models were really correct,” says Dean Pesnell of the Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md. NASA’s lead representative on the panel. “The sun is behaving in an unexpected and very interesting way.” Read story here.

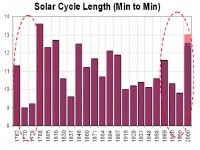

Icecap Note: Other forecasters (Clilverd and Archibald) have an even quieter cycle like that of the s0-called Dalton Minimum with a maximum nearer 40. NCAR’s Dikpati is still holding out for an active cycle 24. The last few cycles including this ultralong cycle 23 (larger image here) mimics the cycles of the late 1700s and early 1800s much as Clilverd and Archibald showed, leading up to the Dalton Minimum, the age of Dickens with winter snows in London (hmmm).

May 26, 2009

No scientific “consensus” about “global warming”

By Bob Ferguson and Lord Christopher Monckton, SPPI

WASHINGTON--(BUSINESS WIRE)—The Science and Public Policy Institute (SPPI) in Washington reports that a leading expert on climate and former advisor to Margaret Thatcher as UK Prime Minister, has dismissed as false a recent claim by the Washington Post that “most scientists now say there is a consensus about climate change”; that warming is “unequivocal”; and that most of the warming of the past century was manmade.

Christopher Monckton, in a new paper for SPPI entitled Unequivocal ‘Consensus’ on ‘Global Warming’, says:

“There is ... no sound or scientific basis for the notion, peddled by the Washington Post, that there is a scientific ‘consensus’ to the effect that anthropogenic ‘global warming’ has occurred, is occurring, will occur, or, even if eventually it does occur, will be significant enough to be dangerous.”

The SPPI paper reveals the following facts that are usually overlooked or ignored -

>Science is not done by “consensus”: the argument from consensus is an instance of the Aristotelian logical fallacy known as the “head-count” fallacy.

>The decision by the UN’s climate panel to attribute more than half of the past 50 years’ warming to humankind was taken by an unscientific show of hands.

>The UN’s chapter attributing most of the past half century’s warming to humankind was rejected by most of the UN’s own official reviewers.

>The warming rate from 1975-1998, when humankind might have had some influence, was the same as the rate from 1860-1880 and from 1910-1940, when humankind’s influence was negligible.

>There is no anthropogenic signal at all in the global temperature record.

>For 15 years there has been no statistically-significant “global warming”.

>For 7.5 years there has been rapid but largely-unreported global cooling.

>The greatest warming rate in the past 300 years was from 1645 to 1715, before the Industrial Revolution began. That warming rate was eight times the 20th-century warming rate.

>The warming of the past 300 years is indeed unequivocal, but the mere fact of the warming tells us nothing of its cause. There is no scientific basis for attributing most of it to humankind.

>The notion that “2,500 scientists” personally agreed with the 2007 assessment report of the UNís climate panel is nonsense.

>The largest-ever survey of scientific opinion - the largest to date - found more than 31,000 scientists did not consider the human contribution to “global warming” significant enough to be dangerous.

>Much of the UN’s reports are written by environmental campaigners, not scientists.

Robert Ferguson, SPPI’s president, said: “In a May 19 article by David Fahrenthold, yet again the Washington Post has been caught out publishing false science, selective data, and faulty conclusions. It is time that certain sections of the news media realized that, as every opinion poll shows, fewer and fewer of the public are any longer believing the politically-driven nonsense they write about ‘global warming’”.

Asks Ferguson, “Has the Washington Post resurrected former Post reporter Janet Cook? Instead of fabricating an 8-year-old heroin addict, has Fahrenthold fabricated a “consensus” about global warming science? Like Cook’s story, the Post’s report proves bereft of evidence and reality. On April 17, 1981, shortly after Cook and the Post were exposed, the New York Times editorialized, ‘When a reputable newspaper lies, it poisons the community; every newspaper story becomes suspect.’ We could not have said it better. Even more tragically, these climate fantasies put at risk the economies and liberties of the Western World and the lives of many in the Third World. Where is the accountability?” See story here.

May 22, 2009

The Green Bubble

By Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger

Sometime after the release of An Inconvenient Truth in 2006, environmentalism crossed from political movement to cultural moment. Fortune 500 companies pledged to go carbon neutral. Seemingly every magazine in the country, including Sports Illustrated, released a special green issue. Paris dimmed the lights on the Eiffel Tower. Solar investments became hot, even for oil companies. Evangelical ministers preached the gospel of “creation care.” Even archconservative Newt Gingrich published a book demanding action on global warming.

Green had moved beyond politics. Gestures that were once mundane--bringing your own grocery bags to the store, shopping for secondhand clothes, taking the subway--were suddenly infused with grand significance. Actions like screwing in light bulbs, inflating tires, and weatherizing windows gained fresh urgency. A new generation of urban hipsters, led by Colin Beavan, a charismatic writer in Manhattan who had branded himself “No Impact Man,” proselytized the virtues of downscaling--dumpster-diving, thrift-store shopping, and trading in one’s beater car for a beater bike--while suburban matrons proudly clutched copies of Michael Pollan’s In Defense of Food and came to see the purchase of each $4 heirloom tomato at the farmer’s market as an act of virtue.

For those caught up in the moment, the future seemed to promise both apocalypse and transcendence in roughly equal measure. The New York Times and San Francisco magazine ran long feature stories on the uptick of upper-middle- class professionals who worried to their therapists about polar bears or who dug through the trash cans of co-workers to recycle plastic bottles, as though suffering from a kind of eco-OCD. At the same time, folks like Pollan and Beavan provided a vision of green living that seemed to offer not just a smaller carbon footprint but a better life. Amid the fear was the hope that the ecological crisis would bring us together and make us happier.

And then, almost as quickly as it had inflated, the green bubble burst. Between January 2008 and January 2009, the percentage of Americans who told the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press that the environment was a “top priority” dropped from 56 percent to 41 percent. While surveys have long showed that enthusiasm for all things green is greatest among well-educated liberals, the new polling results were sobering. For the first time in a quarter century, more Americans told Gallup in March that they would prioritize economic growth “even if the environment suffers to some extent” than said they would prioritize environmental protection “even at the risk of curbing economic growth.” Soon thereafter, Shell announced it would halt its investments in solar and wind power.

Of course, environmentalism itself has not disappeared. Earth Day was celebrated last week, magazines and marketers continue to use green to sell to upscale audiences, and legislation to cap carbon emissions, albeit heavily watered-down, could still pass Congress. But the cultural moment marked by the ubiquity of green self-help, apocalypse talk, and cheery utopianism has passed. It is tempting to reduce this retrenchment to economic pressures alone, with concrete short-term concerns trumping more abstract worries about the future. But a closer look at the causes of the green bubble reveals a more complicated story, not just about the nature of environmentalism but about modern American life itself.

Green anti-modernism brings with it other contradictions. Despite the rhetoric about “one planet,” not all humans have the same interests when it comes to addressing global warming. Greens often note that the changing global climate will have the greatest impact on the world’s poor; they neglect to mention that the poor also have the most to gain from development fueled by cheap fossil fuels like coal. For the poor, the climate is already dangerous. They are already subject to the droughts, floods, hurricanes, and diseases that future warming will intensify. It is their poverty, not rising carbon-dioxide levels, that make them more vulnerable than the rest of us. By contrast, it is the richest humans--those of us who have achieved comfort, prosperity, and economic security for ourselves and for our children--who have the most to lose from the kind of apocalyptic global-warming scenarios that have so often been invoked in recent years. The existential threat so many of us fear is that we might all end up in a kind of global Somalia characterized by failed states, resource scarcity, and chaos. It is more than a little ironic that at the heart of the anti-modern green discourse resides the fear of losing our modernity.

Nonetheless, it has become an article of faith among many greens that the global poor are happier with less and must be shielded from the horrors of overconsumption and economic development--never mind the realities of infant mortality, treatable disease, short life expectancies, and grinding agrarian poverty. The convenient and ancient view among elites that the poor are actually spiritually rich, and the exaggeration of insignificant gestures like recycling and buying new lightbulbs, are both motivated by the cognitive dissonance created by simultaneously believing that not all seven billion humans on earth can “live like we live” and, consciously or unconsciously, knowing that we are unwilling to give up our high standard of living. This is the split “between what you think and what you do” to which Pollan refers, and it should, perhaps, come as no surprise that so many educated liberals, living at the upper end of a social hierarchy that was becoming ever more stratified, should find the remedies that Pollan and Beavan offer so compelling. But, while planting a backyard garden may help heal the eco-anxieties of affluent greens, it will do little to heal the planet or resolve the larger social contradictions that it purports to address. Read much more of this insightful look into the Green Bubble.

|